Mike Coburn Soldier Five Pdf Printer

Phonetic numerals. Numbers are spoken digit by digit, except that exact multiples of thousands may be spoken as such. For example, 84 is 'AIT FOW ER,' 2,500 is 'TOO FIFE ZE RO ZE RO,' and 16,000 is 'WUN SIX TOUSAND.' The date-time group is always spoken digit by digit, followed by the time zone indication. For example, 291205Z is 'TOO NIN-ER. Among my personal copies of the Mike Zeck’s Classic Marvel Stories Artist’s Edition from IDW Publishing, I have 3 copies of the “Sketch Variant” remaining. All are noted as Artist’s Proofs (A/P) on the remark page which was printed for this edition only.

Britain's government has spent five years trying to gag Mike Coburn. His account of an SAS mission that went wrong is more about truth than heroics, reports Nick Ryan. Bravo Two Zero. For many people those three words conjure up the image of the soldier hero: the special-forces trooper - the kind of cool-minded killer who could go anywhere and seemingly do just about anything.

It was the call sign for a British Special Air Service (SAS) patrol during a mission in the 1991 Gulf War that was 'compromised' behind enemy lines. Three of the eight-man team were killed, and four captured and tortured, while trying to destroy Scud missile launchers in north-west Iraq. One managed to escape by foot across the desert into Syria.

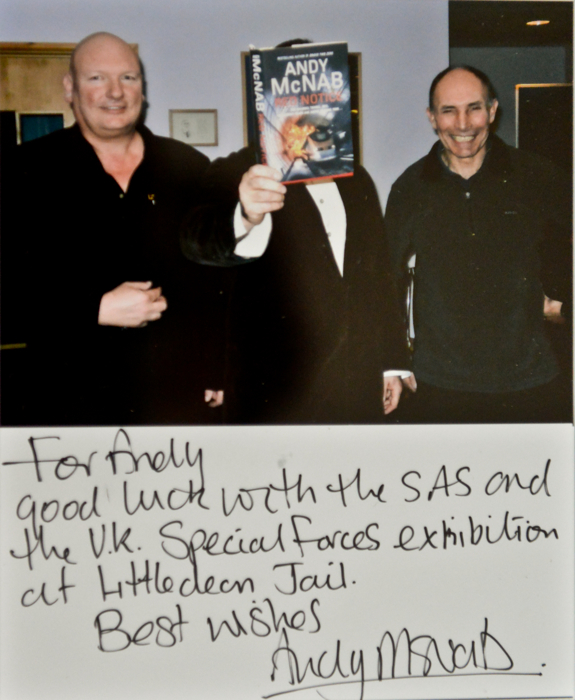

For Andy McNab, the patrol's leader, and Chris Ryan, the soldier who escaped - both names are pseudonyms - the military blunders led, ultimately, to remarkable financial success. Bravo Two Zero, McNab's lionised account of the mission, which was published in 1993, sold millions of copies and launched a slew of copycats. Ryan followed with his story, entitled The One That Got Away. Vetted and approved by Britain's Ministry of Defence (MoD), the books have become an almost sacred part of British military and public myth. Even now posters on the London Underground proclaim the virtues of McNab's latest novel, while Ryan has been busy fronting a BBC television series and promoting an exercise guide. For some, though, the memories of that time refuse to die. For the family of the late Sergeant Vince Phillips in particular, who have had to live with his vilification, particularly in Ryan's book, for 'compromising' the patrol by failing to kill a young goatherd and for seeming to 'give up' after they were split and the men tired.

Others, too, have been haunted by such memories: those who have so far kept silent. 'Did you like the bit about us blowing up all those tanks?' The words are friendly enough, but the eyes are flat, the irony and sarcasm clear in the New Zealander's voice. He is joking about previous Bravo Two Zero accounts as we sit in an almost unbearably hot London apartment. 'I've just got in from Asia,' says the former SAS trooper, who uses the pen name Mike Coburn, by way of explaining the heat, as he offers a glass of wine and settles barefoot on the sofa. Like many former SAS men Coburn is now a security consultant. He seems no Rambo.

About average height, stocky, with dark hair and open features, he served first in his native New Zealand SAS - 'I took to it like a duck to water' - before treading an 'unofficial' path to join the mother regiment in England. He was seeking some real action, and Bravo Two Zero was his first operational mission. Aside from a clear intelligence, there is little that would distinguish him from the man in the street.

Yet if you believe the British government he is a dangerous person indeed. 'Oh, if bin Laden wasn't around I'd be enemy number one,' he says. 'I've no doubt about it. The way they've gone after me over the years is amazing.' Coburn's crime has been to write a powerful account of what he says happened during Bravo Two Zero. Soldier Five, his book, is ostensibly a straightforward, albeit absorbing tale of one man's ordeal during a mission that went badly wrong.

From the outset, however, it's clear that Coburn's version of events (written with another patrol member, an Australian known simply as Mal) is different from previous accounts: he is captured, shot and tortured, but there is none of the heroics of killing the enemy that feature in McNab and Ryan's work. His is a more sombre, seemingly truthful story, which also differs markedly over the role and fate of the late Vince Phillips.

'His brother had a nervous breakdown and his father died a broken man as a result of what happened to Vince,' Coburn says. 'People were quite happy to lay the blame with somebody they knew couldn't answer.' Coburn is withering about the leadership and intelligence failures that led the team to be dumped on a main supply route, almost on top of their target, where they were soon spotted. With no vehicles, they then discovered that none of their communications equipment was working. Not only that, they had also been given the wrong escape route and were then left as expendable once the higher-ups knew something was wrong. Forced to retreat on foot, they became split up and were killed or captured as they made for the Syrian border. Attempts at rescue were fatally delayed.

Shades of Blackadder Goes Forth ensue when the surviving members are told that their commanding officer has graciously decided not to have them court-martialled. Such a chain of failures, not to mention the abandonment of all the usual back-up procedures, is unprecedented, argues Coburn, and is one of his main motivations for writing the book. 'I think the final catalyst was when I was speaking to a former SAS officer who'd overheard a conversation between two commanding officers. They were discussing the call for the patrol to be extracted and classed that as premature. That decision, basically, cost the lives of three men.'

But aren't you supposed to be expendable? Isn't that the law of the special forces? 'There's always an element that you may have to sort out yourself in the end,' he replies, 'but for people to turn back at headquarters and say they're not even going to try anyway, well that's just not acceptable in any way, shape or form.

If you're going to put people in harm's way, you've got a duty to do your utmost to get them back. And if you're not, you've got to tell them.' 'Emotionally, financially, it's been a very difficult five years, no doubt about it,' says Coburn. 'Perhaps weaker relationships wouldn't have survived. It's very stressful.

Of course, in theory this will be the last ever book by an SAS insider that will come out. Because no guy since 1996 who signed that contract can write a book unless the MoD allows them to do it.' As I get ready to leave, he fixes me with that direct gaze and adds: 'You know, this is another thing: Bravo Two Zero is a piece of insignificant military history. The controversy that surrounds it is well out of proportion to the deed.

I was involved in a lot more operations that were more significant and more rewarding. As I said before, I find it remarkable that it actually came to this.' Soldier Five: The Real Truth About The Bravo Two Zero Mission is published by Mainstream Publishing, £17.99 in UK Nick Ryan is creative producer of the new BBC drama England Expects.

This article is about the actual events. For the book by Andy McNab, see.

For the film, see. Bravo Two Zero was the of an eight-man patrol, deployed into during the in January 1991. According to Chris Ryan's account, the patrol were given the task of gathering intelligence, finding a good lying-up position (LUP) and setting up an (OP):15 on the Iraqi (MSR) between and North-Western Iraq, while according to another, the task was to find and destroy Iraqi missile launchers along a 250 km (160 mi) stretch of the MSR.:35 The patrol was the subject of several books. Accounts in the first two books, one by patrol commander Steven Mitchell (writing under the pseudonym ), (1993) the other by Colin Armstrong, writing under the pseudonym Chris Ryan – (1995) as well as those by the SAS's at the time of the patrol, ( Eye of the Storm, 2000), did not always correspond, leading to accusations from the media of lying. The investigative book The Real Bravo Two Zero (2002) by followed the patrol route and interviewed witnesses. The subsequent book, by patrol member Mike Coburn, was released in 2004.

For Mitchell's conduct during the patrol, he was awarded the, whilst Armstrong, and two other patrol members (Steven Lane and Robert Consiglio) were awarded the. Patrol members. Bravo Two Zero patrol members. From left to right: Ryan, Consiglio, MacGown (obscured), Lane, Coburn (obscured), Mitchell (obscured), Phillips, Pring (obscured)., patrol commander:1 former.:21 Captured by the enemy, later released. Author of (1993), and referred to as 'Andy McNab' in the books. Vincent (Vince) David Phillips,:208 patrol:3 former.:30 Died of during action, 25 January 1991.:213,:19 (pseudonym of Colin Armstrong) former 23(R) SAS.

The only member of the patrol to escape capture. Author of (1995).:22 Ian Robert 'Dinger' Pring former.

Captured by the enemy, later released. Robert (Bob) Gaspare Consiglioformer:32:19. Killed in action, 27 January 1991.:172 Steven John 'Legs' Laneformer of, and former Parachute Regiment.:19 Died of during action, 27 January 1991.:226 Malcolm (Mal) Graham MacGown, former.

Captured by the enemy, later released. Referred to as 'Stan' in the books. 'Mike 'Kiwi' Coburn' (pseudonym) former. Captured by the enemy, later released. Author of (2004). Referred to as 'Mark the Kiwi' in the books.

The patrol Background In January 1991, during the prelude to the, were stationed at a in. The Squadron provided a number of long-range, similarly tasked teams deep into Iraq including three eight-man patrols; Bravo One Zero, Bravo Two Zero and Bravo Three Zero.:16 Asher lists one of the three patrols as Bravo One Niner,:37 though it is not clear whether this is one of the same three listed by Ryan.

This article refers to the Bravo Two Zero patrol. Insertion On the night of 22/23 January, the were transported into Iraqi airspace by a helicopter, along with Bravo One Zero and their vehicles.:39 Unlike Bravo One Zero, the patrol had decided not to take vehicles. According to Mitchell's account, the patrol walked 20 km (12 mi):55 during the first night to the proposed location of the observation post. However, both Ryan's and Coburn's accounts put the distance at 2 km (1.2 mi). Eye-witness accounts of, and Asher's re-creation support the Ryan/Coburn estimate of 2 km (1.2 mi). Whilst Ryan states the patrol was intentionally dropped only 2 km (1.2 mi) from the observation post because of heavy pack weights.:29 According to both Ryan and Mitchell, the weight of their equipment required the patrol to 'shuttle' the equipment to the observation post.:95 Four members would walk approximately 300 m, then drop their and wait. The next four would move up and drop their Bergens, then the first four would return for their jerry cans of water and bring them back to the group, followed by the second four doing the same.:42 In this manner, each member of the patrol covered three times the distance from the drop off to the observation post.

Soon after the patrol landed on Iraqi soil, Lane discovered that they had communication problems and could not receive messages on the patrol's radio. Mitchell later claimed that the patrol had been issued incorrect radio frequencies;:393 however, a 2002 report discovered that there was no error with the frequencies because the patrol's transmissions had been noted in the SAS daily record log. Lays the blame for the faulty radios on Mitchell as, being the patrol commander, it was his job to make sure the patrol's equipment was working. Compromise In the late afternoon of 24 January, the patrol was stumbled upon by a herd of sheep and a young shepherd.

Believing themselves compromised, the patrol decided to withdraw, leaving behind excess equipment. As they were preparing to leave, they heard what they thought to be a tank approaching their position. The patrol took up defensive positions, prepared their, and waited for it to come into sight. However, the vehicle turned out to be a, which reversed rapidly after seeing the patrol. Realising that they had now definitely been compromised the patrol withdrew from their position. Shortly afterwards, as they were exfiltrating (according to Mitchell's account), a firefight with Iraqi Armoured Personnel Carriers and other forces developed. In 2001, interviewed the family that discovered the patrol.

The family stated the patrol had been spotted by the driver of the bulldozer, not the young shepherd. According to the family, they were not sure who the men were and followed them a short distance, eventually firing several warning shots, whereupon the patrol returned fire and moved away. Asher's investigation into the events, the terrain and position of the Iraqi Army did not support Mitchell's version of events, and excludes an attack by Iraqi soldiers and Armoured Personnel carriers.

Coburn's version, partially supports Mitchell's version of events (specifically the presence of one ) and describes being fired upon by a 12.7 mm heavy machine gun and numerous Iraqi soldiers. In Ryan's version, 'MacGown also saw an armoured car carrying a machine gun pull up.

Somehow, I never saw that.' ':53 Ryan later estimated that he fired 70 rounds during the incident. Emergency pickup The British (SOPs) state that in the case of an emergency or no radio contact the patrol should return to their original infiltration point, where a helicopter would land briefly every 24 hours. This plan was complicated by the incorrect location of the initial landing site; the patrol reached the designated emergency pickup point, but the helicopter never appeared. Later revealed that this was due to an illness suffered by the pilot, while en route, necessitating his abandoning his mission on this occasion. Because of a malfunctioning emergency radio, that allowed them only to send messages and not receive them, the patrol did not realise that while trying to reach overhead allied jets, they had in fact been heard by a US jet pilot. The jet pilots were aware of the patrol's problems but were unable to raise them.

Many were flown to the team's last known position and their expected exfiltration route in an attempt to locate them and to hinder attempts by Iraqi troops trying to capture them. Exfiltration route Standard operating procedures mandate that before an infiltration of any team behind enemy lines, an exfiltration route should be planned so that members of the patrol know where to go if they get separated or something goes wrong. The plans of the patrol indicated a southern exfiltration route towards. According to the SAS daily record log kept during that time, a transmission from the patrol was received on 24 January. The log read 'Bravo Two Zero made TACBE contact again, it was reasonable to assume that they were moving south,' though in fact the patrol headed north-west towards the border.

Myfourwalls mac serial numbers, cracks and keygens are presented here. No registration is needed. Just download and enjoy. Myfourwalls mac keygen. MyFourWalls 1.0.5 for Mac + Crack - Furnishing planner.

Coburn's account suggests that during the planning phase of the mission, Syria had been the agreed destination should an escape plan need to be implemented. He also suggests that this was on the advice of the Officer Commanding B Squadron at that time. According to Ratcliffe, the change in plan nullified all efforts over the following days by allied forces to locate and rescue the team. Mitchell has also been criticised for refusing advice from superiors to include vehicles in the mission (to be left at an emergency pickup point) which would have facilitated an easier exfiltration. Another SAS team used in this role when they also had to abandon a similar mission. However, it is also suggested that the patrol jointly agreed not to take vehicles because they felt they were too few in number and the vehicles too small (only short-wheelbase Land Rovers were available) to be of use and were ill-suited to a mission that was intended to be conducted from a fixed observation post. Separation During the night of 24/25 January,:118 while Mitchell was trying to contact a passing aircraft using a communicator, the patrol inadvertently became separated into two groups.

Light support machine gun Each member of the patrol wore a uniform, with a era sand-coloured desert smock.:37 While the other members had regular issue army boots, Ryan (the only member to avoid eventual capture) wore a pair of £100, 'brown -lined walking boots.' :38 Each member carried a, one sandbag of food, one sandbag containing two, extra ammunition bandoliers and a 5 imp gal (23 l) jerry can of water.:29:66 'The belt kit contained ammunition, water, food and trauma-care equipment.' . Ryan, Chris (1995). The One That Got Away. London: Century.

McNab, Andy (1993). Bravo Two Zero.

Great Britain: Bantom Press. 14 December 1998. Retrieved 18 April 2014., The London Gazette (Supplement), Gazettes online (54393), p. 6549, 9 May 1996, retrieved 25 October 2011. Asher, Michael (2003). The Real Bravo Two Zero.

England: Cassell. Coburn, Mike (2004).

Soldier Five. Great Britain: Mainstream Publishing.

Lowry, Richard S (2003). The Gulf War Chronicles. Cowell, Alan (5 March 1991).

The New York Times. Retrieved 25 October 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

Moss, Stephen (12 March 2004). The Guardian. Retrieved 25 October 2011. The New Zealand Herald. Maguire, Kevin. Retrieved 25 October 2011. Taylor, Peter (10 February 2002).

Retrieved 25 October 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011. Swindon Advertiser.

Mike Coburn Soldier Five Pdf Printer Software

Retrieved 29 October 2011. The Independent. 7 December 2000.

Retrieved 25 October 2011. The New Zealand Herald. Clarke, Shaun (1993). Soldier A: SAS - Behind Iraqi Lines. Great Britain: 22 books.

Mike Coburn Soldier Five Pdf Printers

Fowler, Will (2005). SAS Behind Enemy Lines: Covert Operations 1941-2005.

London: Collins.